Interviews & Profiles

Peking to Paris in a '69 VW Beetle

Jun 29, 2011

It was the dawn of the automobile age, when a Paris newspaper issued this challenge in 1907: "What needs to be proved today is that as long as a man has a car, he can do anything and go anywhere. Is there anyone who will undertake to travel this summer from Peking to Paris by automobile?" Five teams accepted the challenge, and so began the storied history of the Peking to Paris motor race, a wild, globe-hopping contest that covered 9,000 miles of uncharted terrain and at a time when there were few roads. The winning car was an Italian-made car called the Itala with a seven-liter engine and oversized separate oil tank for the total-loss engine lubrication system.

A rebuilt version of the winning Itala participated in the 2010 race, along with just over 100 other classic cars -- including a 1918 Stutz Bearcat, 1925 Ford Model A, 1929 Rolls Royce Phantom, 1935 Bentley, 1939 Packard, 1949 Cadillac, 1965 Aston Martin (James Bond's car), and 1969 Volkswagen Beetle. Gernold G. Nisius, 51, a Mercedes-Benz restorer in Arundel, Maine, was the refurbished Beetle's mechanic and navigator (though he also shared driving chores with the car's owner Garrick D. Staples, who lives in southern California).

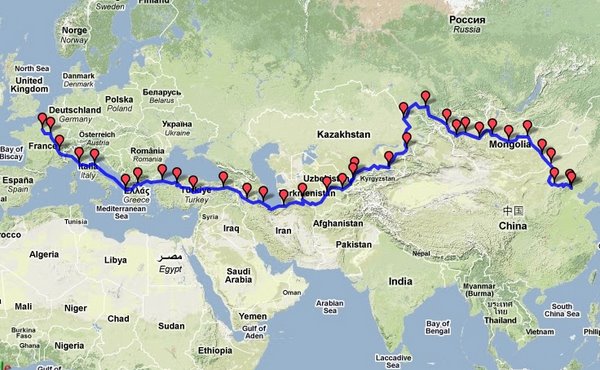

Held intermittently over the years with course routes determined by regional conflict and political tension rather than terrain, the 2010 Peking to Paris rally started in Beijing, crossed Mongolia and the Gobi desert, then followed a route that loosely followed the ancient Silk Road, including Kazakhstan, Uzbekhistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Turkey, Greece, Italy, and finishing in Paris. France. There were mandatory rest stops each night. Mechanical break- downs were common, though about 90 percent of those cars that started P2P finished, including the durable Beetle that had modified Baja-like suspension. "This was a grueling event with no time to spare and can only be compared to doing the Paris Dakar without support vehicles," says Gernold. Given obvious space limitations, he brought few personal belongings. "After 50 days on the road, all with two pairs of RailRiders Versatac Light Pants, one Expedition Shirt and my beloved Equator-HT Shirt. The Versatacs performed flawlessly."

RailRiders: What made you decide to enter the rally?

Gernold Nisius: I read a book about the race and decided that's something I should do. I then went to their website and found out there was a category where people offer cars for sale or their services as a navigator and a mechanic. I decided to do the same and then within a few weeks, I had numerous inquiries from people looking for a navigator and mechanic. This all happened two years prior to the 2010 rally. The whole preparation took almost two years. And they can only have a rally like this every this every three years at a minimum.

RR: Why?

GN: That's what it takes them to prepare the route. It's the longest vintage long-distance rally anywhere. There really is no winning at the end because when you get to Paris there's too many different classes. You've got cars that start in 1907 up to the newest cars built in 1968. Making it to Paris for me was everything. It's almost like running the Paris-Dakar without any support. There is really no overall winner and to many different classes and to me everybody that made it to Paris was a winner. You're in the car, two people, you've got it packed up with everything you need. They have three support vehicles called Sweepers; they come from the back and if you broke down, they stop and they've got a few spares and tools and they're there to help you, but they're not required to get you going or to tow you or anything. So you're pretty much on your own. If your car breaks down and you can't get it going again, the rally leaves the next day, and you sit there. That makes it pretty stressful.

RR: Your car one of the latest models?

GN: Actually, it was registered in California as a `69 Beetle, but they allowed it in the end because it was all prepared. But `68 is really where they cut it off; they don't want anything newer.

RR: Did you have any mishaps?

GN: We were pretty lucky in the Beetle. We had very few problems. We broke the roll bar in the car from all the rattles. Once it didn't run right in the Mongolian desert, but we fiddled with it for two hours and got it going again; I could never really figure out why it wouldn't run. We had a similar experience later in the rally and my take was a electrical fault in the wiring somewhere. But that had been a real tough day as far as the road conditions -- all washboard. We came in after the maximum allowed lateness, and so we got the whole day scrapped. We essentially lost our standing that day. We were leading that class up until then, and after that we lost what was called the Gold Standard.

RR: What did you do to specially outfit the Beetle?

GN: The Beetle was completely restored. Garrick Staples who owned the car already had done most of the work and he did a very good job for a amateur mechanic. He lives in the L.A. area. I went there three or four times for a week to spend time with the car, just looking it over, but most of it was rebuilt. It had a few changes, like a full roll bar, Porsche seats, GPS system, different suspension -- almost like a Baja race car where the shocks come right through the body into the roll bar.

RR: How did your own body handle it?

GN: I didn't have any problem. I'm physically very fit. Of course, the better shape you are in, the better it is.

RR: Did you have to pay an entry fee?

GN: Yes. The entry fee for one car is $50,000. Garrick paid for it.

RR: Where did you sleep at night?

GN: Other than Mongolia and I think one or two camps in the "Stan" countries, we always had very good hotels. We went to eleven countries. The rally organizer picked some of the best hotels they could find. The organizer thought it was always important to have the cars safely secured.

RR: What was it like to go across Western China and Mongolia?

GN: Mongolia was the best part of it. We were there for nine days. It's just a wide-open country.

RR: You mentioned the rough terrain.

GN: Yes, the emphasis of the rally is to break the car. They don't want you to make it to Paris; they made sure we used the lousiest roads they can find. If there is a good road, we're not on it. That's how that works.

RR: How many cars finished in Paris?

GN: I think ninety-five made it out of the one hundred and seven cars that started.

RR: That's a very high percentage.

GN: Yeah, it is. Everybody is trying to somehow get this thing to Paris. I found out after the rally that one couple flew their car from someplace in Mongolia to Kazakhstan in a plane for $30,000! The car broke and they wanted to gain some time to fix the car and get going again. There were all kinds of other dramas. Cars broke down; people had no way to get a part and so they had parts flown into different countries by friends. Some of these cars were very valuable. There was a 1935 Bentley Speed Six; it's a million-dollar car.

RR: What about the Aston Martin, the car that James Bond drives as 007?

GN: It also did very well. That car was actually in the rally before; the owner spent $200,000 preparing it for the rally.

RR: And then they trash these expensive classics in the rally. Explain to me that psychology because it seems confusing.

GN: This is a real rich man's game. But most of the people with these cars, they have enough disposable income. There was very few people hanging on like I did, just as a navigator and mechanic, who spent ten, fifteen thousand dollars, which is not that much if you think about it for six weeks. But some of these people with these cars, they have enough money.

RR: Talk about the 1907 Itala that was in the race.

GN: That Itala had been there in 2007. An English couple, David and Karen Ayre, found that car by accident on some farm. For years, they didn't know really what it was until they discovered that a sister car actually won this rally. So they changed it around, made it look exactly like that car that won in 1907. Of course, the rally organization liked that, and that's why you constantly see pictures of that car.

RR: Do the couple wear the same kind of goggles and clothes from the early 1900s?

GN: Yeah, they were really dressed for the role -- the whole outfit. They had the leather boots, with laces up to their knees. They are a really nice couple and I really liked them a lot.

RR: I noticed that there was a number of Rolls Royces in the rally. How did they do?

GN: They did very well. That's a very tough car. Most of the older cars made it through, but there was plenty of repairs on the side of the road. A lot of cars lost all kinds of suspension parts and needed constant repairs. Every night right after you came to the hotel or to the camp, you worked on the car. We were pretty lucky because the Beetle is a durable car and it didn't really need that much and it's very simple. You open the rear deck and you look at the engine, there's not much there.

RR: But you don't have much cargo room for your body.

GN: Oh, it's a pretty small car. There wasn't much there. You can't carry all that much. That's why we pretty much lived with one outfit or two maximum - you wash one, you wear the other. RailRiders came in handy!

RR: How many miles did you average per day?

GN: In Mongolia, we did about two hundred miles a day and in the other countries, sometimes three, four hundred.

RR: Did you ever get lost, make a wrong turn?

GN: The whole rally is described in three books that look like a Sears catalog. The organization of this rally is phenomenal. Every inch of the day is mapped out and timed with the trip meter, and you can follow it and its 99.99 percent accurate. So if you follow your books and know how to operate your GPS you never really get lost.

RR: So you didn't have On Star!

GN: No, but what was mandatory was a satellite phone - they introduced that in 2007 because in the first modern rally, I think in 1997, they had people getting lost; they couldn't find them for three days.

RR: How did the media treat you? As heroes?

GN: Oh, yeah, everywhere we went there were interviews, especially the smaller Stan countries, which for them was a big deal. There were kids on the road waving.

RR: Did you experience any problems with border crossings?

GN: One day we crossed the border into Russia and due to the formalities and with three hundred people crossing the border, we caused a lot of hiccups there. So crossing into Russia took about six hours. We left the border that day at 4:00 pm and had 550 Miles to go to the next hotel. We got there at 2:30 am and left again at 7:00 am the next morning.

RR: Did anyone get into any serious accidents?

GN: One Bentley got in an accident right in the beginning in China. Another car got in a pretty bad accident in Turkey in the fog. He went straight instead of taking a right bend, and the car went straight down the hill for two hundred feet.

RR: What happened to the drivers and the car?

GN: They had to bring in a backhoe to get the car out of the ditch. It was totaled.

RR: And the two of them?

GN: They were okay, but they were shocked, really shocked. They were lucky because the hill flattened out in the bottom, so they kind of rolled out of it.

RR: There was little media overage of the rally in the United States.

GN: I'm German. I came here when I was thirty years old. Your motor sports is totally different here. It's all geared to this country and if you want to watch people go around a circle. I'm not a fan of that.

RR: What other adventurous things have you done?

GN: I've hiked in the altitude in Nepal. I've been to New Zealand for a whole month motorcycling with a friend. I've been planning a motorcycle trip to Alaska.

Gernold arriving in Paris in style-- and in his RailRiders clothing after 9,000 miles on the road.